The Clock Jobber's Handybook

By Paul N. Hasluck

Brought to you by:

Tick Tock Productions ™

The

CLOCK JOBBER'S HANDYBOOK.

PENDULUMS

THE CONTROLLERS.

CHAPTER III

ESCAPEMENTS COMMONLY USED.

ESCAPEMENTS deserve the most careful consideration from clock-jobbers, as the escapement of a clock has great influence on the entire mechanism. Clocks will not perform regularly if there be errors in the construction 'of the escapements, no matter how perfect all the other mechanism is. The motive force, after it has been transmitted through the entire train of wheels, reaches the escapement so enfeebled that it must be utilised to the best advantage. The large treatise on Modern Horology, by Claudius Saunier, is devoted chiefly to the consideration of escapements. An English translation of this valuable book is now published by Messrs. Crosby Lock- wood and Son, and every horologist could learn something by a careful perusal of its contents. I am indebted to this book for some of the information forming the substance of this chapter.

Escapements used for clocks of various kinds are usually comprised under three varieties, viz.:—recoil, dead-beat, and detached. Recoil escapements, in which the supplementary swing of the pendulum, after a tooth has escaped, causes a backward motion to the escape-wheel. Dead-beat escapements, in which the tooth of the escape-wheel falls on a pallet face forming an arc of a circle struck from the centre of motion of the pallets; in this the escape-wheel remains "dead" during the supplementary swing of the pendulum. Detached escapements, in which the escape-wheel does not act directly on the pallets, excepting during a very brief period; this form of escapement is used mostly for turret clocks, and others in which the motive power is variable in its force. All these varieties of escapement have peculiar characteristics, and each is advantageous for certain purposes; it will therefore be useful to give a description of each one.

Recoil escapements are most frequently used in ordinary household clocks, such as eight-day English clocks. Robert Hook is credited with the invention of the recoil or anchor escapement in the latter half of the seventeenth century. Reid, in his Treatise on Clock and Watchmaking, published in 1826, thus points out the properties of the recoil escapement. When the teeth of the escape-wheel drop or fall on either of the pallets, these, from their form, cause all the wheels to have a retrograde motion, opposing, at the same time, the pendulum in its ascent, the descent being equally promoted from the same cause. This recoil, or retrograde motion of the wheels, which is imposed on them-by the re-action of the pendulum, is sometimes nearly a third, sometimes nearly a half or more, of the previous advancement of the movement. This is perhaps the greatest or the only defect that can properly be imputed to the recoil escapement. It is the cause of the greater wearing in the holes, pivots and pinions, than that which takes place in a clock having the dead-beat escapement. This defect may partly be removed by making the recoil small, or a little more than merely a dead-beat.

After a clock with a recoil escapement has been brought to time, any additional motive force that is put to it will not greatly increase the arc of vibration, yet the clock will be found to go considerably faster. It is known that where the arc of vibration is increased even but very slightly, the clock ought to go slower. The force of the recoil pallets tends to accelerate and multiply the number of vibrations according to the increase of the motive force impressed upon them, and hence the clock will gain on the time to which it was before regulated. Professor Ludlam, of Cambridge, who had four clocks in his house, three of them with dead-beat escapements and the other with recoil, said, "That none of them kept time, fair or foul, like the last; this kind of escapement gauges the pendulum, the dead-beat leaves it at liberty."

The reader must recollect that this was written upwards of fifty years ago. In the last handbook on watches and clocks published, dated a few years ago, we read of the recoil escapement that, when well made, it gives very fair results, but the pallets are often very improperly formed, although none of the escapements are easier to set out correctly. There are still people who believe the recoil to be a better escapement than the dead-beat, mainly because a greater variation of the driving power is required to affect the extent of the vibration of the pendulum with the former than the latter. But the matter is beyond argument; the recoil escapement can be cheaply made, and is a useful escapement, but unquestionably it is inferior to the dead-beat for time-keeping.

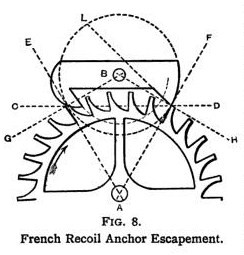

The instructions for setting out a recoil escapement given in The Watch And Clockmaker's Handybook are as follows:— Draw a circle representing the escape-wheel, which we assume to have thirty teeth, of which number the anchor embraces eight. Mark off the position of the fourth tooth on each side of a vertical line drawn through the centre of the wheel; draw radial lines, which will represent the backs of the teeth. The position of the teeth is easily ascertained by a protractor, thus:—the space between the teeth is equal to 360° divided by the number of teeth, that is 360/30 = 12°. There are seven spaces between eight teeth, so that the space to be marked off between the teeth is equal to 12° x 7, that is 84°; half of this on each side of the vertical line will be 42° from the 90° line on the protractor.

The

centre of the motion for the pallets is at a point, on the vertical line,

fourteen-tenths of the radius of the escape- wheel from the centre of it;

that is to say, measure the radius of the escape-wheel, add four-tenths of

the distance, and mark a point on the vertical line which will show the

centre of the pallets. From the centre of the pallets draw a circle

through the points of the teeth marked on the circumference of the

escape-wheel. The arc of this circle will be found to bisect the vertical

line midway between the centre of the pallets and the centre of the

escape-wheel. From this circle, struck from the centre of the pallets,

draw tangents through the points of the teeth that are marked. These

tangent lines show the positions for the faces upon the pallets, but these

faces are always rounded somewhat in practice. The pallets are cut off at

those points which allow half the impulse to each, that is, when one tooth

drops off one pallet, the point of the other pallet is just midway between

two teeth.

The

illustrations of the recoil escapement show this. The form of teeth shown

in the escape-wheel is adopted, so that if the pendulum is swung

excessively, the points of the pallets butt against the thick roots of the

teeth, and do no injury, as they would if the teeth were nearly straight,

and the motion of the pendulum arrested by the face of the pallet butting

on the tops.

The diagrams, Figs. 8 and 9, show how to draw a recoil escapement. These illustrations are lettered to facilitate the description ; and if any reader has a clock provided with this form of escapement, which he suspects to be faulty, it will be very easy to draw a diagram showing accurately the proper form, and then compare it with the actual dimensions and shapes of the various parts.

Learn clock repair with these DVD courses! Course manuals are included.

Watch, study and learn antique clock repair through DVD course instruction using actual live repairs!!

Clock Repair 1 & 2 Advanced Clock Repair PRO advanced clock repair

Clockmaker Watchmaker Lathe Basics Clockmaker Watchmaker Lathe Projects Clock Case Repair & Restoration Wooden Works Movement Repair

© Copyright 2001-2009 by Tick Tock Productions © Copyright 2001-2009 by John Tope All rights reserved.

Back to clock information page.

Hasluck, Paul N. The Clock Jobber’s Handybook. London: Crosby Lockwood and Son, 1889.

This and the following pages are excerpts from the book.